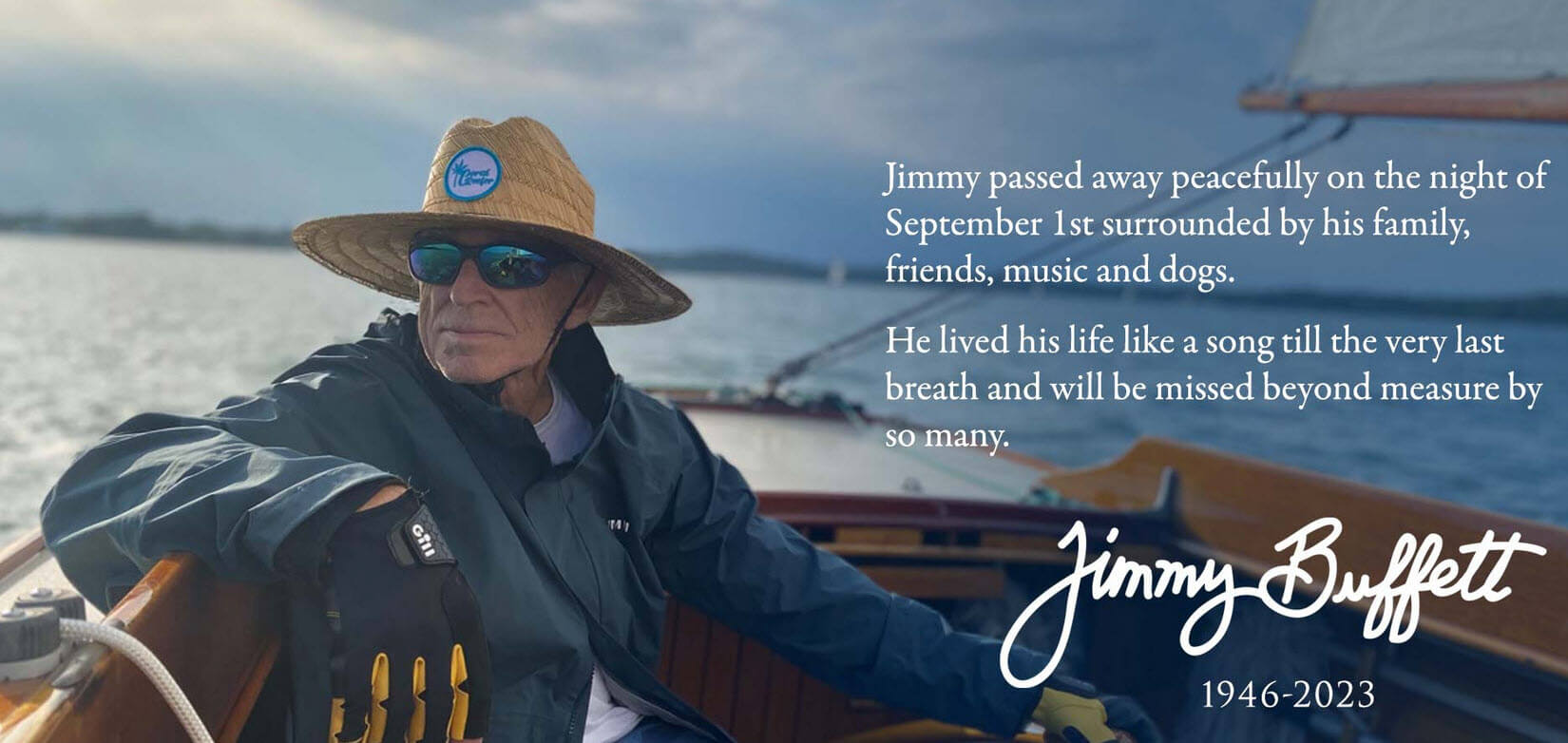

Jimmy Buffett died on September 1, 2023, at age 76 after a diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (skin cancer) four years earlier. He was a renowned singer-songwriter, film producer, businessman, novelist, and philanthropist.

Buffett released his first album, Down to Earth, in 1970. By 2023, his net worth was officially $1 billion,1 including a $180 million stake in his company, Margaritaville Holdings LLC, which opened in 1985 and now brings in $1 to $2 billion annually.

Who Stands to Inherit Buffett’s Estate?

Buffett had an early, three-year marriage to Margie Washichek before divorcing in 1972 and marrying Jane Slagsvol in 1977. He and Jane had three children: Savannah, Sarah, and Cameron. The children have all pursued careers in the music, film, and entertainment industries.

According to the New York Times, most of Buffett’s money and property, including intellectual property and music rights, are held in a trust.2 His wife, Jane, is the personal representative distributing the estate according to his will, with help from his business partner and Margaritaville Holdings LLC CEO, John L. Cohlan, if necessary. Because the trust provides the family with privacy, there are no specifics regarding which belongings will be passed to his wife, three children, two grandchildren, and two siblings. His estate is estimated to include the following3:

- Music royalties of $20 million annually

- A collection of houses and cars

- 150 Margaritaville restaurants, casinos, cruises, and related business holdings

- A yacht and several planes

- Stock market investments, including shares in Berkshire Hathaway

- Watches and memorabilia

Buffett was still receiving close to $200 million annually for his shares in Margaritaville Holdings LLC, and it seems that issues with his health and medical expenses did not affect his business or family legacy. He was still growing his wealth when he died.

Other Estate Planning Strategies Buffett Could Have Included Beyond His Will

Buffett co-founded the Save the Manatee Club in 1981 with former Florida governor Bob Graham, supporting rescue, rehabilitation, research, and education efforts in the Caribbean, South America, and West Africa. During his lifetime, Buffett gave away and helped raise millions of dollars for charities. For every concert ticket he sold, one dollar went to a charitable cause he believed in.4

Charitable Remainder Trusts

Given his charitable actions during his lifetime, Jimmy Buffett may have had a charitable remainder trust (CRT) to incorporate charitable giving into his estate. This type of trust could serve to secure his family’s future by providing a consistent income source to his beneficiaries while ultimately honoring his charitable nature by leaving the remainder to the charity of his choice.

Family Limited Partnerships or Family Limited Liability Company

Buffett likely considered his restaurants to be much more than commercial enterprises—and business continuity may have been preserved by creating a family limited partnership (FLP) or family limited liability company (LLC). Utilizing one of these types of entities could have allowed him to use different strategies to retain control over his business shares while gradually transferring ownership to his wife and children. He could have also potentially taken advantage of the annual gift tax exclusion by making tax-free gifts of the limited partnership and mitigating potential future estate tax implications.

Grantor Retained Annuity Trusts

A grantor retained annuity trust (GRAT) may have been another trust structure that Buffett considered to pass down his business interests while retaining certain financial benefits during his lifetime. A GRAT is an irrevocable trust that would have allowed him to transfer his business interests or other assets with the potential for significant appreciation in value to the trust while still retaining an income stream for himself via annuity payments for a specified term. At the expiration of the term, his beneficiaries would receive any assets from the trust, with any excess appreciation above the § 7520 rate transferred free of estate and gift taxes.

Family Trusts

After years of ongoing use and enjoyment of the property he owned, Buffett could have also taken steps to ensure the smooth transfer of assets such as his airplanes to future generations for their own use and enjoyment by establishing a family trust. A family trust would have allowed him to designate how the planes should be used, maintained, and cared for after his death.

In a well-designed estate plan, the things that someone owns, such as Buffett’s planes, money, and other significant property, would avoid probate, thereby maintaining the family’s privacy. Additionally, the beneficiaries would not have to wait to wrap up lengthy or costly court proceedings before inheriting the things Buffett intended them to receive.

Long-Term Care Planning and Advance Directives

Buffett had plenty of funds to pay for his long-term care needs privately, but he may have set aside specific financial resources intended to pay for care in advance if he consulted with a professional advisor or estate planning attorney earlier in his life. Based on comments made by his family in his final days, he may have also prepared advance directives so everyone understood his wishes for care and treatment at the end of his life. Consequently, he appears to have made a peaceful exit from a terminal illness on his own terms.

While Buffett’s life may be over, he leaves behind a substantial legacy. Keep an eye out for the posthumous release5 on November 3, 2023, of the album Equal Strain on All Parts, featuring guest contributions from Paul McCartney, Emmylou Harris, Angelique Kidjo, and the Preservation Hall Jazz Band.

Footnotes

- Jessica Tucker, Here’s How Much Jimmy Buffett’s Estate Is Worth (and Who Stands to Inherit It), TheThings (Sept. 8, 2023), https://www.thethings.com/how-much-was-jimmy-buffett-worth/#.

- Julia Jacobs, Jimmy Buffett’s Will Appoints His Wife as Executor of His Estate, N.Y. Times (Oct. 13, 2023), https://www.nytimes.com/2023/10/13/arts/music/jimmy-buffett-will.html.

- Gabbi Shaw & Jordan Parker Erb, Jimmy Buffet Became a Millionaire after 5 Decades in the Music Industry. Here’s How the Late Singer Made and Spent His Fortune, Insider (Sept. 2, 2023), https://www.insider.com/jimmy-buffett-billionaire-makes-and-spends-his-money-2023-4.

- Id.

- Megan LaPierre, Jimmy Buffett’s Estate Announces Posthumous Album Equal Strain on All Parts, Shares Three Songs, Exclaim (Sept. 8, 2023), https://exclaim.ca/music/article/jimmy_buffetts_estate_announces_posthumous_album_equal_strain_on_all_parts_shares_three_songs.