A primary goal of estate planning is to financially provide for your loved ones. One way to ensure that they are set up for lifelong success is with an inheritance that pays for their education.

Higher levels of education are positively correlated with better life outcomes, including improved health, longer lifespans, and higher incomes.[1] However, education costs across all levels have risen significantly, pushing a good education out of reach for many families and saddling students with debt that can take decades to pay off.[2]

From primary school to postgraduate studies, you can invest in a loved one’s education and maximize their potential through your estate plan. Options include direct payments, 529 plans, and money from a will or trust, often with associated tax breaks.

While educational gift options abound, their legal mechanics, tax implications, and benefits differ depending on when and how they are given, and restrictions may apply.

Higher Education = Greater Well-Being—but at What Cost?

The economic and noneconomic benefits associated with a college degree are well established.

Compared with people who completed only a high school diploma, those with undergraduate degrees not only earn significantly more on average over their lifetimes and are less likely to be unemployed but also tend to enjoy better health and a higher quality of life, including higher job satisfaction, improved self-esteem, improved access to healthcare, and increased civic engagement.[3]

According to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics, people with a bachelor’s degree earn two-thirds more than high school graduates.[4] Over the course of their working years, college graduates typically earn around $1 million more than their degreeless peers.[5]

Although the economic advantages of a college degree vary based on the degree earned[6]—and despite the rising costs of postsecondary education—most Americans recognize the value of college and view a degree as a “golden ticket” to prosperity.[7]

However, earning a college degree has never been more expensive, and these costs are forcing some Americans to rethink whether it is worth the investment.

Tuition and fees have tripled since the 1960s, jumping by 60 percent between 2000 and 2022, from around $9,000 to nearly $15,000 per year.[8] From 2010 to 2022, average annual tuition and fees went from $12,979 to $14,688—a 13 percent increase.[9]

These rising costs, which include room and board, books, and other supplies in addition to tuition, are discouraging many students from attending college and contributing to enrollment declines.[10]

The average federal student loan debt balance in 2024 was nearly $40,000, while the total average balance (including private loan debt) is even larger.[11] Today, the typical public university student borrows almost $32,000 to earn a bachelor’s degree.[12] Far from the “golden ticket” of a degree, student loan debt can limit wealth building and upward mobility instead of opening doors.

Costs are also rising at K–12 private schools, which are generally considered a gateway to higher education. Research shows that private schools are better than public schools at preparing students to enter college, most likely due to their higher scores on standardized tests and more-demanding graduation requirements.[13] However, the average annual private school tuition is $12,000–$13,000, including about $9,000 for private elementary school and roughly $16,000 for private high school.[14]

Today, a student who attends private schools from kindergarten through four years of postsecondary study can expect to pay more than $300,000.[15]

As college enrollment declines, trade programs are picking up the slack. Trade and vocational schools are usually a much cheaper option than a traditional four-year college. Programs cost approximately $5,000 to $20,000 and are often completed within two years.[16] Enrollment in these programs, which many young people see as a quicker and more affordable path to a good job, has seen strong growth, including double-digit increases in some fields.[17]

In addition, students who take advantage of internships and externships while in college have improved employment prospects.[18] However, even a paid internship can impose costs on students, such as housing, transportation, and other living expenses.

Family Contributions Are Vital to Achieving Educational Goals

Families are a significant funding source for education at all levels. For example, parents contributed an average of $13,000 per year toward undergraduate education costs.[19] Family financial help can also play a major role in paying for trade school, private K–12 school, and internship-related expenses.

Every dollar a family invests in a loved one’s education alleviates their potential debt burden and fast-tracks their future success. To make your legacy a launchpad for their achievements, consider the following educational gifts and their potential tax benefits:

- Direct tuition payments. Tuition paid directly to an educational institution is not considered a taxable gift.[20] This exemption applies to K–12 schools, colleges, and trade schools but covers only tuition—not room and board, books, or other expenses. It allows parents, grandparents, or other relatives to contribute without using their annual or lifetime gift tax exclusion.

- 529 plans. Contributions grow tax-free, and withdrawals for qualified educational expenses (tuition, fees, books, room and board, computers) are also tax-free at the federal level. Since 2018, funds from 529 plans can be used for K–12 tuition (up to $10,000 per year). Some states offer tax deductions or credits for contributions, and, starting in 2024, unused funds can be rolled into a Roth IRA for the beneficiary (subject to limits).

- Coverdell education savings accounts (ESAs). Contributions (subject to limitations and capped at $2,000 per year per beneficiary) are not tax-deductible, but earnings grow tax-free if used for qualified educational expenses, from kindergarten to higher education, including tuition, fees, books, supplies, tutoring, and certain technology needs, and they provide flexible investing options.

While tax benefits make it appealing to use those savings for a loved one’s education, not all education-related expenses fit the rules laid out above. Some expenses happen outside the classroom and may impose additional student costs that families can help cover. For example:

- Internships and externships. Even if the program pays the participant a small sum, the amount may not cover the expenses associated with participating in the program, such as rent (if the program is in a different city or state), food, insurance, etc.

- School field trips. Depending on the trip, the cost to participate can be expensive. Setting aside money for your loved one to participate in such activities can allow them to have additional life experiences that will shape them even after you have passed away.

You can support your loved one’s future by setting aside funds in a trust specifically for these types of expenses.

Gift Timing

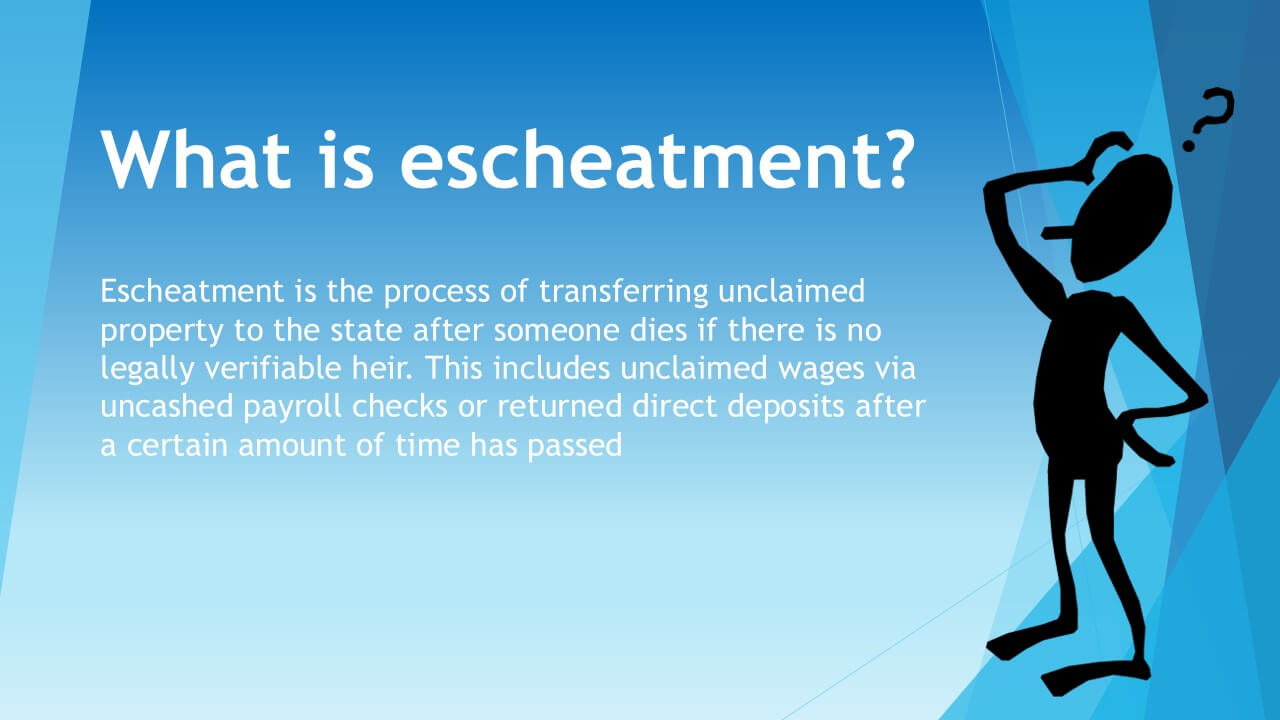

Education funding can take place during your lifetime or after you die. Lifetime gifts use gift tax rules. Postdeath gifts fall under estate tax rules that are applied at death.

However, because the lifetime gift and estate tax are unified, using one affects the other, and lifetime and postdeath estate planning strategies should not be viewed separately. You might, therefore, use a mix of lifetime and posthumous educational gift strategies. Consider these common scenarios:

During Life

- Direct tuition payments. You can pay tuition to an educational institution at any time while you are alive, and it is immediately exempt from gift tax.

- 529 plans. You can establish and fund a 529 plan while alive, taking advantage of tax-free growth over time and the ability to front-load five years’ worth of annual exclusions ($95,000 in 2025). You control the account and can adjust beneficiaries as needed.

- Payments to loved ones for a specific purpose. Currently, you can give $19,000 per year per recipient tax-free during your life for any purpose, including nontuition expenses such as internship costs or field trips, reducing your taxable estate while you are alive.

After Death (via Will or Trust)

- Direct tuition payments. You can set up a will or trust to allocate funds for tuition, directing your executor or trustee to pay educational institutions on behalf of a loved one.

- 529 plans. You cannot fund a 529 posthumously through a will because it is a lifetime savings vehicle tied to a living account owner. However, you could name a successor owner (e.g., a spouse or child) for an existing 529, or your estate could distribute funds to a beneficiary who then opens a 529, though this option loses the predeath tax-free growth benefit. After your death, the executor of your estate or the successor trustee of your trust can distribute the funds to an existing 529 plan, depending on what your will or trust instructs and what funds are available. Note that the contributions from a will or trust will not qualify for the gift tax exclusion and will still be part of the taxable estate. It is also important to clearly name the account beneficiary and owner, since the account owner will control how the funds are used.

You might also consider using a trust created via your will (testamentary trust) or funded during your life (revocable living trust) that offers gifting flexibility. You can instruct the trustee to pay for tuition, tech, or living expenses, mimicking lifetime strategies. Trusts can also be tailored (e.g., “pay tuition directly to schools” or “distribute $10,000 yearly for education”).

Whether it incorporates a gifting-while-living strategy or a standard inheritance, your estate plan can unlock the power of education while leveraging tax breaks. Schedule a meeting with us today to discuss specific strategies and which one is best for you and the student in your life.