The idea of one-size-fits-all no longer fits a world where people expect products and services to be tailored to their individual preferences.

The estate planning world, long rooted in tradition, has relied on time-tested tools such as trusts to plan for what happens to a person’s money and property. However, a nontraditional variation known as a directed trust has gained traction in recent years for offering today’s families more of what they want: customization, control, and flexibility.

Although directed trusts have existed in the United States since the early 1900s, a modern legal framework for this type of trust structure that was adopted in the past decade has helped fuel their increased use. This updated approach divides trust administration duties between trustees and advisors, allowing for more personalized and effective administration.

Trust Versus Directed Trust: What Is the Difference?

A traditional trust has three key parties:

- Grantor: The person who creates the trust and transfers their money and property into it

- Trustee: The individual or institution responsible for managing the trust’s accounts and property, making distributions, filing taxes, and ensuring that the trust’s terms are carried out

- Beneficiaries: The people or organizations that receive the accounts and property from the trust

Under this structure, the trustee holds unilateral authority over—and full legal responsibility for—the trust. As the trust’s primary decision-maker, the trustee handles investments, manages day-to-day administration, and distributes funds according to the trust’s instructions. All these tasks must be done while honoring the trustee’s duty to always act in the beneficiaries’ best interests, an obligation that can sometimes present challenging legal and ethical hurdles.

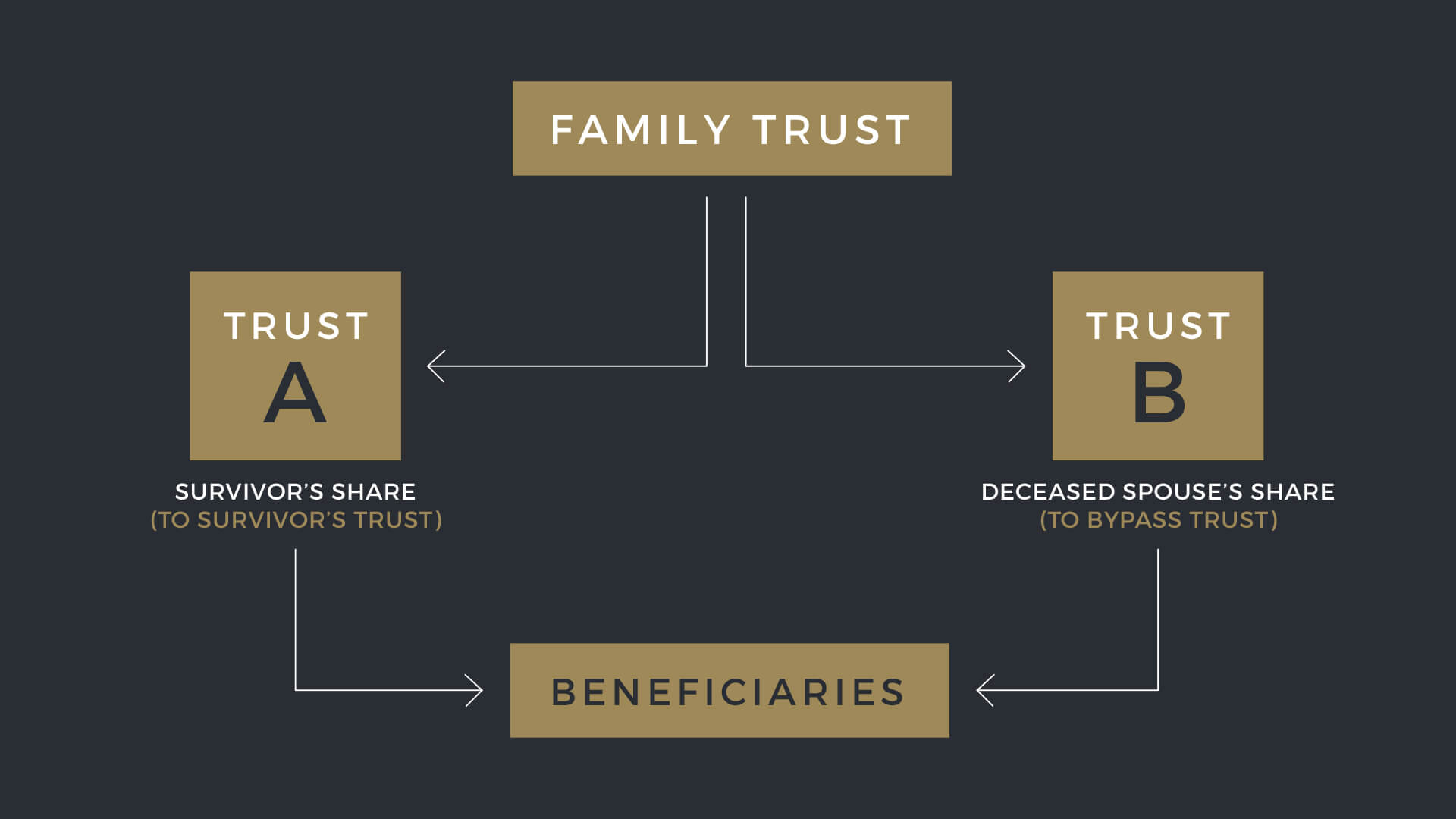

A directed trust keeps the same basic structure but divides the trustee’s duties among multiple parties. Instead of a single trustee who does it all, the grantor can appoint the following:

- An investment advisor to direct how the trust’s accounts and property are invested

- A distribution advisor to oversee when and how beneficiaries receive funds, according to the trust’s instructions

- An administrative trustee to handle compliance, taxes, and reporting

The popularity of directed trusts tracks with a broader societal shift toward greater complexity in family structures, diverse types of financial accounts and property, and a growing need for specialized expertise. While trusts have been around for centuries and can be written with provisions that offer some degree of flexibility, the idea of splitting trustee duties is a later innovation that allows for greater specialization and nuance.

What Are the Benefits of a Directed Trust?

Choosing a trustee is one of the most important decisions a grantor can make in an estate plan. The trustee is entrusted to safeguard and grow the trust’s assets and ensure that they are ultimately transferred to the people and causes the grantor has named in the trust document.

A key part of this role involves managing the trust’s accounts and property, including overseeing the trust’s investment portfolio, ensuring that it remains adequately diversified, and structuring it to meet the beneficiaries’ financial goals and needs. However, even corporate or professional trustees may not always be the best fit for investment management, particularly when the trust holds highly specialized assets. For example, a grantor might

- own a family-run manufacturing business in which insider knowledge is essential to good decision-making,

- hold a concentrated position in biotech stocks or digital assets requiring active management by someone familiar with the sector, or

- have a portfolio of commercial real estate investments best overseen by an experienced property manager.

Many trustees work with an investment manager who advises them on the trust’s investment strategy. However, families often already have a long-standing relationship with a financial professional who understands their portfolio and has a proven track record of successfully managing it. Turning investment authority over to a new trustee, who may select their own investment manager, can disrupt that relationship and potentially lead to less favorable results.

Directed trusts address this dilemma by separating investment management from administrative responsibilities. This bifurcation is achieved by drafting the trust so that a preferred advisor named in the document has authority to direct the trustee on investment matters.

A directed trust offers the best of both worlds—the legal and operational advantages of a trust paired with the expertise of the grantor’s chosen financial professional(s):

- Specialized expertise. Appoint advisors who understand unique assets such as a family business or specialized investments.

- Continuity of management. Keep an existing financial team in place to avoid disruptions to long-standing investment strategies.

- Flexibility and control. Tailor trust administration to fit the grantor’s needs and preferences.

- Many possibilities. Structure the various trustee positions and roles in different ways; for example, a directed trust typically includes an investment advisor but can also have multiple advisors in specific areas or a trust protector, who is neither a trustee nor an advisor but is appointed by the grantor to supervise and ensure that the trustee carries out the grantor’s intentions.

A directed trust also benefits the administrative trustee by removing liability and fiduciary duties related to investment decisions for accounts and property held in the trust portfolio.

With fewer fiduciary obligations, someone who might decline the full range of responsibilities of serving as trustee in a traditional trust may be more willing to accept a scaled-down role in a directed trust. This flexibility can give the grantor more options when selecting a trustee.

Are There Any Downsides to a Directed Trust?

All estate planning tools have tradeoffs, and directed trusts are no exception. Despite their flexibility, they have potential drawbacks and may not be suitable for every person’s unique situation. Before setting one up, consider the following:

- Added complexity. Dividing trust duties among multiple parties creates more moving parts and risks the classic “too many cooks in the kitchen” scenario. Clearly defining roles in the trust document helps prevent misunderstandings and administrative bottlenecks. Appointing a trust protector offers an extra layer of oversight but also introduces yet another “cook” to what might already be an overcrowded kitchen.

- Potential for disputes. Having multiple decision-makers for a single trust can increase the risk of conflicts if communications break down. Disputes that cannot be amicably resolved may require court intervention and impose additional costs on the trust.

- Geographical challenges. Not every state recognizes directed trusts, and those that do may have differing laws. While neither the grantor nor their appointed trustee team needs to live in a directed trust state (such as Delaware or South Dakota), it is important to remember that the income tax laws of the state where the trustee resides generally control where the trust income will be taxed. If a directed trust has trustees or advisors in different states—such as a corporate administrative trustee in Nevada and an investment advisor in California—multiple states may claim taxing authority over the trust’s income, which can lead to conflicting tax obligations, higher compliance costs, and added complexity, making careful drafting essential to preserve the intended governing state law.

- Higher costs. Using multiple professionals can increase trust costs. There may be separate fees for the administrative trustee, an investment advisor, and possibly a trust protector.

- Beneficiary confusion. While directed trusts can shield administrative trustees from liability for investment decisions, this division of responsibilities can leave beneficiaries uncertain about who is responsible if issues arise.

How Is a Directed Trust Different from Having Co-Trustees?

The division of decision-making power in a directed trust should not be confused with the shared authority of a trust managed by co-trustees.

- In a co-trustee arrangement, each trustee shares equal authority and responsibility. They must act together (or by majority, depending on the trust’s instructions) to manage the trust’s accounts and property, make distributions according to the trust’s instructions, and fulfill administrative duties. Crucially, each co-trustee has the same ethical and legal responsibility for all aspects of the trust.

- In a directed trust, roles and responsibilities are split by design. Each advisor or trustee has a defined scope of authority (for example, one may oversee investments, another may handle administrative tasks, and a third may control distributions). The administrative trustee has little or no say over investment decisions and is not liable for them, while the investment advisor is not burdened with tax filings or compliance.

The right trust structure—and the right team—can make all the difference for your legacy. Contact our estate planning attorneys to see if a directed trust is the right fit for you.