Retirement can mean many different things to different people. For some, it opens up a new world of travel, experiences, and creative pursuits. For others, it may herald quiet days at home with a good book, a steaming mug of tea or coffee, and no other plans for weeks.

Between those extremes are countless ways to spend one’s postworking years. Like work itself, retirement takes various forms, shaped by practical needs and personal preferences. However, retirement demands one thing above all: adaptability.

While the pace of your days may be slower in retirement, life does not stand still. We are living longer, spending more years in retirement, and dealing with new financial and personal realities. Whether you are approaching retirement or already in it, this stage calls for a fresh look at your estate plan and timely adjustments that match your next chapter.

Retirement Today: Key Trends Shaping Your Estate Planning

Work is not just something we do to make money; rather, we typically see our jobs as a defining part of our identity.

However, no matter how much we may like our jobs, or at least recognize the structure and stability they bring, many of us also find that there is more to life than working. Retirement is supposed to be the reward for a lifetime of hard work, and it still is for many Americans. They turn age 65, start collecting Social Security and enroll in Medicare, and begin to do all the things they never previously had time for.

The retirement picture has changed over the decades. While it theoretically remains the final phase of the American Dream, retirement for most of us looks much different than it did for our parents or grandparents. These differences reflect cultural changes and evolving financial conditions that shape how we live, work, and, ultimately, retire.

Living Longer, Often with Higher Costs

Retirees are living longer, increasing the length of their retirement and their expected healthcare expenses. These factors affect how long savings last and may influence estate planning priorities as well.

- As of 2025, the projected life expectancy for Americans who have reached age 65 is 83 years for men and 86 years for women.1 In 1940, the projected life expectancy for a 65-year-old was 77 years for men and 79 years for women.2

- Today, median retirement savings for households aged 55–64 is about $185,000,3 below many recommended benchmarks.

- About one-third of retirees are very concerned about being able to cover healthcare costs,4 and for good reason. A 65-year-old retiring today could spend more than $170,000 on healthcare alone during retirement.5

Estate Planning Perspective: Due to longer lifespans and rising healthcare expenses, your estate plan may need updates to ensure that your lifestyle and legacy goals are supported well into retirement, including provisions for medical care, long-term support, and financial flexibility.

Retirement Is Not What It Used to Be

Older adults today are often working longer or pursuing encore careers, meaning that retirement does not always start at a set age. Working past traditional retirement age can affect income, assets, and estate-planning timelines.

- The average retirement age is now around age 62, up from age 57 in the early 1990s.6 In 2023, approximately 19 percent of adults age 65 and older were still working, up from 11 percent in 1987.7

- Nearly one in four adults age 50 and above who are still working expect to never fully retire,8 and workers age 75 and older are the fastest-growing age group in the workforce, more than quadrupling in size since 1964.9

- Many retirees pursue part-time work or side ventures,10 adding new assets or income streams to their financial picture.

Estate Planning Perspective: Your estate plan should address your current income, any new assets, and the possibility that retirement may start later or look different than you originally expected.

Fixed Incomes and Savings Pressures

Many retirees rely on fixed income, drawing from Social Security, pensions, or savings. Inflation, market volatility, and healthcare costs can affect how long assets last.

- Nearly 50 percent of adults age 60 and above have household incomes below what is needed for basic living expenses.11

- Inflation hits retirees harder than near-retirees because retiree income often does not rise as quickly as prices do.12

- Approximately 64 percent of Americans are worried that they will outlive their retirement savings.13

Estate Planning Perspective: If you rely on fixed income or are drawing down investments, revisiting your estate plan can help protect both your current lifestyle and the financial legacy you intend to leave for loved ones.

Shifting Family and Lifestyle Dynamics

Downsizing, relocating, or buying new homes later in life is increasingly common, which can significantly affect asset ownership and estate planning priorities.

- Baby boomers, at 42 percent, represent the largest share of home buyers, a significant increase from previous years.14

- A growing number of retirees are embracing multigenerational living, often taking the form of sharing a home with children and grandchildren15 or cohousing, where they live in private homes within a community that shares common spaces and support.16

- More retirees are ditching their homes for recreational vehicles (RVs) and year-round life on the road.17

Estate Planning Perspective: Changes in living arrangements, whether downsizing, moving in with family, or spending extended time on the road, can affect property ownership status, associated taxes, and the effectiveness of your current estate plan. It is important to review how your property is titled, provisions regarding what you would like to happen to your property within any trusts, and beneficiary designations to ensure that all are aligned with your current situation and goals for the future.

Staying Active, Traveling, and Lifestyle Considerations

Living longer and with better overall health means that retirees today are far from slowing down. Between bucket-list travel, volunteering, and new hobbies, retirement is increasingly more about reinvention than rest.

- Senior travel trends include more “golden gap years”18 or long-term travel among retirees.

- Older Americans are getting out more in retirement, with senior participation rates in outdoor activities such as hiking, camping, and fishing showing a marked rise in recent years.19

- A growing number of Americans over 65 are launching small businesses to stay active, pursue passions, and have more control over their work in “retirement.”20

Estate Planning Perspective: A more adventurous, entrepreneurial, and mobile retirement can introduce new risks and responsibilities. Tweaking your estate plan to account for business interests, recreational vehicles, new retirement investments, and contingency plans keeps it aligned with how you live today.

Thinking More Intentionally About Legacy, Gifting, and Long-Term Care

Retirees are increasingly focused on intentional legacy planning, including lifetime gifting and charitable contributions, while balancing higher healthcare costs and the potential need for long-term care as they age.

- More older Americans are embracing a “giving while living” approach to their heirs and inheritance.21 In fact, older people are also the most likely to make donations to charities.22

- Long-term care costs are skyrocketing. Average costs range from more than $150,000 per year for in-home health aide and homemaker services to more than $125,000 per year for a private nursing home room.23

Estate Planning Perspective: As your priorities shift toward value-driven giving, charitable contributions, and planning for long-term care costs, your estate plan should evolve to reflect not only financial goals but also personal values and the impact you want to leave on your family and community.

Revisiting Your Estate Plan: Practical Scenarios for Retirees

While retirees and near-retirees have a sense of the cultural and economic forces that are shaping the current retirement landscape, they may be unsure about how these changes should translate to their estate planning decisions. Here are some real-world scenarios that take into account what retirement means today—and what it might mean for your estate plan.

Longevity and Healthcare Costs

Situation: You are retired, living longer than expected, and facing rising medical or long-term care expenses.

Scenarios to evaluate:

- You find yourself relying more on Social Security or pension income than you had originally anticipated.

- Market fluctuations are affecting the sustainability of your retirement portfolio.

- Healthcare, long-term care, or caregiving costs are higher than anticipated.

Possible estate planning updates:

- Review and update beneficiary designations on your retirement accounts and insurance policies. This is especially important after opening new investment or retirement accounts, rolling over a 401(k) into an individual retirement account (IRA), or purchasing new life insurance or hybrid life and long-term care policies. Even one outdated beneficiary form can derail an otherwise solid estate plan.

- Evaluate tax-efficient withdrawal and distribution strategies, including how required minimum distributions (RMDs), Roth conversions, Social Security timing, and Medicare premium brackets may affect both your lifetime cash flow and the assets ultimately passing to your beneficiaries.

- Review long-term care planning options such as incorporating provisions for incapacity, updating powers of attorney, or considering a trust structure designed to help protect assets from future care expenses (based on your state’s laws and eligibility rules).

Health and Lifestyle Adjustments

Situation: A new medical diagnosis, evolving long-term care needs, or living in multiple states is prompting changes in your medical or personal planning.

Scenarios to evaluate:

- You or your spouse has received a chronic or progressive health diagnosis.

- You want to remain safely at home with appropriate in-home care or are considering assisted living as part of your long-term care strategy.

- You split time between residences in different states—each with different rules for healthcare documents, guardianship, and Medicaid eligibility.

Possible estate planning updates:

- Update healthcare directives and powers of attorney to confirm that your chosen agents are still appropriate and that documents comply with the requirements of every state where you live or may receive medical care. This includes health care proxies, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) releases, and durable financial powers of attorney.

- Revise your living will or advance directive to reflect your current preferences for treatment, end-of-life care, pain management, and life-sustaining procedures.

- Review your long-term care strategy, such as exploring traditional or hybrid long-term care insurance, Veterans’ benefits, or state-specific Medicaid planning strategies designed to help preserve assets while meeting eligibility requirements if care needs escalate.

- Consider trust structures for incapacity planning, such as a revocable living trust or, in some states, an irrevocable trust designed for long-term care or asset protection, depending on the timing of your planning and applicable laws.

- Coordinate medical and legal planning across states, especially if you own real property in more than one jurisdiction or if your primary residence for healthcare purposes differs from your legal domicile.

Property Changes and Relocation

Situation: You sold a long-term residence, acquired new property, or moved to another state.

Scenarios to evaluate:

- You purchased a new primary or vacation home.

- You joined a multigenerational household or cohousing community.

- You relocated to a state with different probate, tax, or property rules.

Possible estate planning updates:

- Retitle newly purchased real estate, vehicles, or other assets in the name of your trust to avoid probate.

- Review estate planning documents under the laws of your new state of residence to ensure compliance.

- Confirm homestead, property tax, or community property implications of your new state of residence.

Family Changes and Evolving Relationships

Situation: A marriage, a divorce, or a birth has shifted your priorities.

Scenarios to evaluate:

- Your children or grandchildren have new partners or are expanding their own families.

- Your stepchildren or other dependents should be added to or excluded from your estate plan.

- You provide ongoing financial support to family members.

Possible estate planning updates:

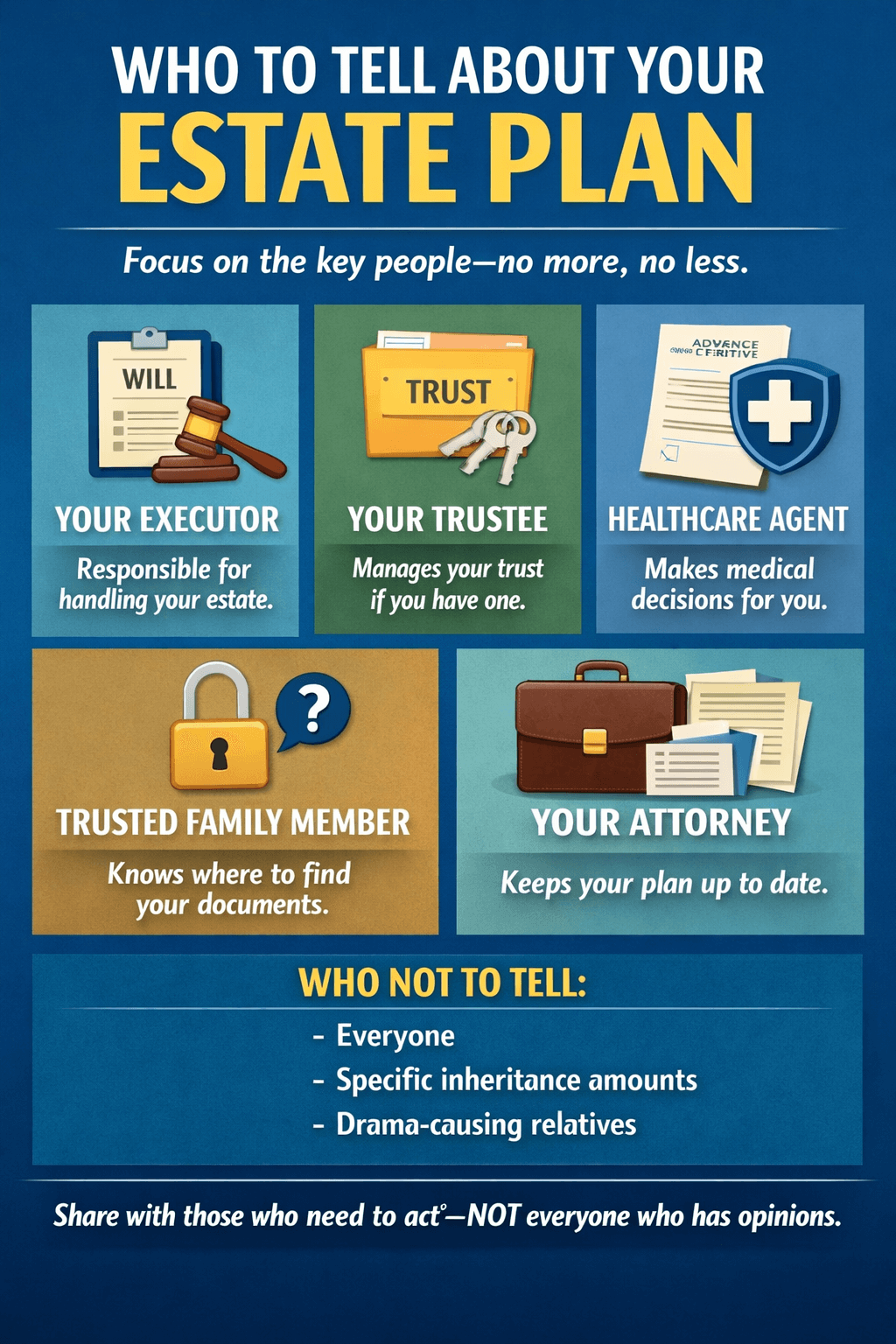

- Revise your will or trust to include or exclude beneficiaries as appropriate.

- Add letters of intent explaining any unequal distributions to help reduce family conflict.

- Update your guardianship, trustee, or executor appointments to reflect current relationships.

Intentional Legacy, Gifting, and Philanthropy

Situation: You wish to give gifts during your lifetime, leave charitable contributions at your death, or pass along personal values to your loved ones.

Scenarios to evaluate:

- You intend to provide financial gifts to family members or loved ones during your lifetime, either annually or through larger strategic transfers.

- You are considering charitable giving, such as donor-advised funds, charitable trusts, or planned bequests.

- You want to document and share your values, life lessons, or hopes for how inherited assets will be used by future generations.

Possible estate planning updates:

- Review your revocable living trust to ensure that it reflects your gifting goals, incorporates charitable intentions, and simplifies the transfer of assets to beneficiaries and charitable organizations.

- Integrate gifting or charitable strategies into your estate plan to optimize taxes and enhance the impact of your legacy.

- Document your legacy beyond the legal documents by creating an ethical will, legacy letter, or family mission statement expressing your values, stories, lessons, and intentions for the assets you are passing on.

- Coordinate with your financial advisorto ensure that gifting aligns with your own financial security, tax profile, and long-term planning needs. Lifetime gifts should support—not undermine—your ability to maintain quality of life.

Planning for Change

The transition to retirement can reshape nearly every aspect of your financial and personal life. Your estate plan should evolve alongside it.

As retirement stretches longer than ever, what once seemed sufficient in your original plan may no longer meet your needs. Lifestyle changes, family dynamics, and financial realities all influence the effectiveness of your estate planning documents. It can be helpful to pause at major life milestones such as retirement to reflect, revisit, and reevaluate how life will be different moving forward and to take actions that support the new circumstances of your next chapter.